In a 5-4 decision, with Justice Scalia in the lead, the Republiscam majority of the Supreme Court held today that non-compliance with constitutional “knock notice” rules did not require suppression of subsequently seized evidence. In practical effect, this means that Murkans have now attained the same status as Iraqis under U.S. liberation.

A little background for those who may have been ignoring the Fourth Amendment for the past decade or two. The amendment requires a judicially issued warrant before government agents can forcibly enter your home, make a mess of it, and seize what they say is evidence of a crime. After all, we all can remember the melodramas of Wehrmacht soldiers stomping around in hobnailed boots, kicking down doors, and we wouldn’t want that in God’s Country now, would we?

As ancillary to the warrant requirement (have-warrant-can-enter), the high court held, in Wilson v. Arkansas, (1995) 514 U. S. 927, that police are also required to knock and give notice of their entry before kicking in doors. The reason is as simple as it is obvious: a warrant to search for evidence of crime is not a license to act like a thug. For this reason, the Court has held that the “reasonableness” of a search and seizure depends as much on the “method of an officer’s entry” as it does on the grounds for entering at all.

As most people have heard, at least from the raving hysterics on Fox News, a violation of the Fourth Amendment requires suppression of the illegally seized evidence. This has been the rule since Weeks v. United States, (1914) 232 U. S. 383. The reason is also as simple as it is obvious: Why have a constitution at all if it can be violated with impunity?

The Constitution requires a president to be 36 years of age when elected. If a 12 year old were elected would it be so absurd to say he should be excluded from taking office? What is not constitutional simply ought not to be, and ought not to be recognized “in contemplation of law” as the quaint but incisive phrase used to have it.

However, in the 1960’s, when the high court was all gaga with this thing called sociology, it invented more scientific sounding reasons for the exclusionary rule. It held that exclusion of illegally seized evidence was required because by loosing otherwise good evidence, cops would be taught an object lesson in good behavior. The prospect of loosing their case because they failed to comply with the constitution would act as an incentive to follow the law.

Of course not only is that sort of heteronomous reasoning a lot of stuff and nonsense, it is also a sword that cuts both ways. Needless to say court conservatives, in lockstep with their boys-in-blue, were quick to argue that evidence should be suppressed only “where its remedial objectives” would be “most efficaciously served,” United States v. Calandra, (1974) 414 U. S. 338, 348) and “where its deterrence benefits outweighed its ‘substantial social costs.’” (United States v. Leon, (1984) 468 U. S. 897, 907.) What these marbles in-the-mouth meant was that if judges could think of some plausible sounding reason why cops did not need to have their knuckles wrapped, the evidence need not be suppressed.

So now we come to today’s decision in Hudson v. Michigan (June 15, 2006) No. 04–1360. Looking to maximum efficaciousness, the Republiscam majority held that suppressing evidence on account of police failure to give knock notice was outweighed by the “social costs” of doing so.

Hudson was not a case involving terrorism. Why it was not even a case involving code purple Kiddie Porn. It was a garden variety drug seizure case. If the social costs of loosing a routine drug case outweigh unconstitutional behavior, it is hard to see what kind of misbehaviour the cops have to commit in order to warrant a constitutional sanction.

The majority was evidently troubled by the subjectivity of this how high is too high approach; and so it fashioned a test which was just as bad. It held that evidence should not be suppressed unless the illegality complained of was the “but for” reason for the seizure. In plain language, if the cops lied in order to get the warrant and if the warrant was the basis for seizing the evidence, then the exclusionary rule would take effect. On the other hand, if the police used a SWAT team to blast away the front of a house as the method for serving the warrant, that misbehaviour would not call for a constitutional sanction. How the warrant is served is something different from why the warrant was served, and the Bill of Rights protects only the “why” not the “how”. At least, thus sprach Scalia.

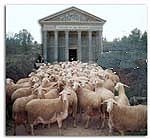

Every day, Iraqis are subjected to having their homes burst into without so much as a knock... at least not that kind of knock that doesn’t come from the heel of a boot. Without an effective deterrence on thug-behaviour, Murkans can expect little more from the Kevlar Boys patrolling their streets.

But not all hope is lost. The Republiscam majority did continue to recognize that the primary reason for the “knock notice” rule “is the protection of human life and limb, because an unannounced entry may provoke violence in supposed self defense by the surprised resident.” Supposed? There is little to “suppose” about a smashing sound at the door. The court recognizes that people who smash down doors court the risk of being blown away by people on the other side who have a natural, human and constitutional expectation of security in their own homes.

©JustinLaw, 2006.